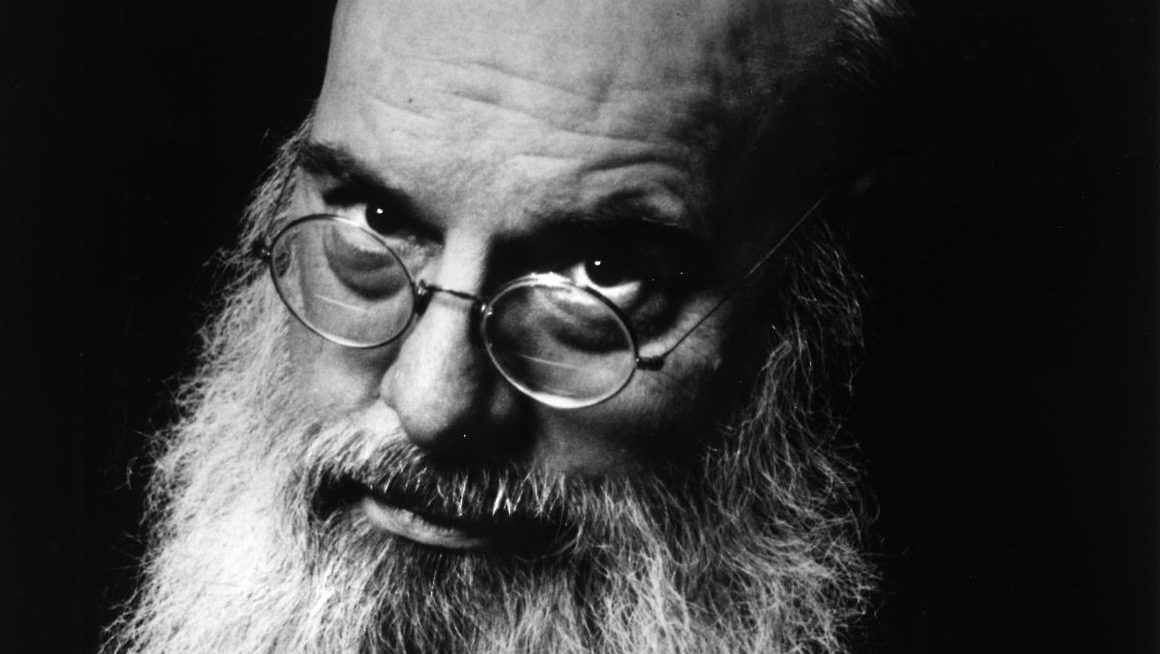

Eugene

The death of Eugene Burger, a legend of modern magic, has just been announced.

Much will be said in the magic community about Eugene’s passing. I cannot think of another figure in our strange and wonderful world who was (and is) as loved, who loved as much back, or who truly gave himself up to the stuff of mystery. He inspired a generation of close-up magicians – including me, very directly – and will continue to do so. When I first met him as a novice, he taught me a great lesson in how to make magic feel special. We later became friends, and though I lived too far away to count myself amongst his close companions, we would see each other when we could and had a lot of love for each other.

Yet there is something else surrounding his death that has struck me, which may be passed over amidst the eulogies, and may even sound a little strange to say now. And that is, that his death was somehow suitable.

As a magician, Eugene was a master storyteller. His magic hooks you in because it weaves a narrative around the possibility of deep mystery. In life we weave stories continuously: in order to navigate the infinite data source of our environment we must edit and delete and reduce an active, messy world to a neat story that makes sense of what’s going on. We tell ourselves stories of who we are, how we got to where we are, what we want, what other people want, what they think of us. If we are mindful, we might try to see our story-telling capacity at work, and remind ourselves that we are continuously twisting the facts to fit whatever story has gripped us. We should of course own our narratives, but we might also choose to be aware that they remain just that, otherwise they have a tendency to own us.

Eugene seemed to be a man in charge of his own story, yet mindful of its contingency within a world of deep mystery. When we are not, we are usually beset by needs and forever chase external approval and goals that continually elude us. By comparison, Eugene lived with a minimum of possessions (he knew little of the collecting mania which drives many of us in our field) and seemed to have no particular ambitions beyond the grateful enjoyment of the here and now. If you know his work but never met him, he was exactly as you’d want him to be, and then some. I found this almost too good to be true: I wanted to understand how the love for magic could continue to run so deep in this brilliant, philosophical man, without a hint of the weary cynicism of which we are all guilty. How it was to find his only family in the magic community. But throughout, there was only the warmth and ease of a man very at home with himself and his world. I never felt even a hint of the bitterness one might expect from a magic legend who remained more or less unknown to the public at large. There was no suggestion of jadedness, or pretension, or the bewildering egomania that pervades our craft. He had of course his distinctive look, but he was never affected, never contrived (after all, he always had that look: I imagine he emerged with beard and garb fully dressed from the womb, greeting a world that would come to adore him with a rasping basso tremendo). The aura that surrounded Eugene (on stage as well as off) was one of twinkling mischief, of naughtiness, of gravitas without solemnity. Perhaps most powerfully he carried that air about him that the most charismatic actors often bring to their parts: that of I have a secret. It was irresistible.

He appeared to me a man profoundly at home with himself; one who had made a comfortable space for whatever demons still undoubtedly announced themselves on occasion. And unheard of for a magician: he didn’t try to impress. But his masterstroke of story-telling was that of his ending.

Mystery lies in ambiguity. Eugene said towards his end that he was excited to finally meet the Big M Mystery. How profoundly that statement must have moved his friends; how beautifully a lifelong reverence for mystery served him at the end. It is in our last chapter of life that the importance of authoring ones narrative is paramount. When a book or film ends, it makes sense of what has come before. When a life ends, there is no meaning: often only absurdity. We have to find that meaning for ourselves. It is hard to do this if we see death as a terrifying stranger rather than as a companion, and nothing in our culture encourages us to make our peace with its ever-presence. Since we proudly stripped away superstitions from our thinking a few hundred years ago, we have all but lost touch with any cultural narratives that provide a sense of meaning around death. Hence the proliferation of mediums and psychics, who step in to provide some tawdry semblance of significance. Eugene’s séances by comparison offered only further mystery.

So we scrabble blindly when death approaches, and in doing so, we often become cameos in our own stories. The main roles are given over to doctors or loved ones who make decisions for us and above all try to prolong life, which is quite different from preserving its quality. The only narrative the dying person is offered today is that he or she is ‘fighting a brave battle’, and this only helps the healthy onlookers feel a little better. For the terminally ill person it is an imposition, which adds pressure to seem brave for everyone else’s sake. And of course it presupposes eventual failure.

I could not read his mind, despite the promises of our professions, but by all reports Eugene died as a man in charge of his own story. I spoke to one of his dearest friends (and doctor) soon after his passing: I am told Eugene had nothing but deep gratitude for a life that surpassed all his expectations. Unattached to possessions, he adored the hospital rooms with which he had become quite familiar, marvelling at the food and how well he was looked after. Mortality had become a comfortable theme for him, and when a cancer diagnosis came he declined to fight it with chemotherapy. Pneumonia arrived instead, and continuing the theme of a life well lived, he took a quiet ownership of death too. A lifetime of loving and of gathering people together meant that he finished his life in the way he wished. He died very well.

Finally, it’s rare one gets to choose ones family, but Eugene was able to do this. And this family of close friends will now miss him terribly. Yet nothing that burns so brightly is snuffed out easily. Eugene deeply affected so many people: those dearest loved ones and partners in magic, his friends, his students, those who have learnt from his books and videos, the audiences who have loved his performances, and the magic world which will honour him. Eugene knew that the self is not fixed but malleable, ambiguous and situated: it extends into the world. So we should honour this. He is not absent: we can still find him in all of those people. When we die, we leave behind an afterglow in the hearts and minds of those who loved us. Eugene’s afterglow will be felt for a very long time.

Those who were closest to him will recall and settle in their reveries of Eugene; they will now and then feel what it would be like to be him, to laugh at what he would laugh at, to react or raise an eyebrow or ponder a thought in his way. When they do, they will recreate in themselves the particular pattern, the unique twinkling consciousness that defined him. The more sympathetically they knew him, the more him it will be. And maybe this is where we find the Big M: perhaps it is something to do with the love between people that provides the mechanism for the self to survive death in the only meaningful way we know.

In those moments, in each of those imperfect, invisible versions of Eugene that will spring into life within those who know what made him him, his distinctive Eugene-ness will appear again. And again, and so on, through all of us, and over a very long, slow fade.

August 2017

wonderfully put Derren

Beautifully said!

Thank you for writing this piece, Derren. While I only had the chance to see Mr. Burger lecture once many years ago, I think it’s fair to say that he has left such an important mark on our art form that it has helped shape all magicians who came after him. He will be missed deeply.

It seems to have become incredibly dusty in here all of a sudden. It’s allergies, just allergies.

Proof of a life well lived, is having just one person talk so fondly as this Derren. Beautifully written.

Beautiful and eloquent and just gorgeous.

Very beautiful and so very true! Your letter made me cry but also helped me feel better!

I will miss my dear friend and our monthly dinners and frequent phone calls. But Eugene will always be in my heart! Thank you for these wonderful, thought-provoking words! Well done!

Thank you for this Derren – it is a beautiful summation of a beautiful man. I was lucky enough to meet Eugene on several occasions and his generosity and willingness to spend time with this rank amateur will always remain in my memories.

It may seem an odd thing to say, but I also have Eugene to thank in part for the fact that I am now some 95lbs lighter than I was some 12 months ago. Talking to him at the Mystery School about how he had lost weight gave me encouragement to follow his lead and his advice.

I spent a short time with Eugene along with a small group of others over a period of a week, and even though it was short I can now see exactly what you are saying about his character, that naughtiness and constant holding of a secret. Great insight, well written.

This is a beautiful piece. You moved me to tears. – Michael Close

Thank you for this.

Derren, what a soaring, moving tribute; specific to Eugene, but also gloriously encompassing all humanity..

He loved most things and most people, and he surely would have loved your words.

This is beautiful and kind.

Like so much of what have said and written in the past, this is profound. But, more so than all the rest. Thank you, Derren.

A gorgeous elegy. As a magician member of the Magic Castle, Eugene and I got acquainted when he read my Houdini-Conan Doyle play and called me to express how much he enjoyed it. After that, when he was in LA, he would be at the Castle, and he would always take the time to step away from the throngs who clung to him to chat with me. To say that Eugene was adored is an understatement, but you’ve completely captured him and his remarkable and witty and generous aura. There never was — and never will be — anyone like Eugene.

Beautifully written… amen

What a splendid tribute. I met Eugene once. He was walking round the Northern Quarter in Manchester, where I work. I raced out to meet him, shake his hand and tell him how much he’d inspired me. Of course my mind went blank and all I could say was, “It’s you!”. And in his deep, gravelly voice he replied, “Yes, and it’s you, what a coincidence”. Anyhow, we had a good chat, he was great!

Wow Derren … perfect x

That was the most beautiful thing I’ve read in a long ti.e

Thank you

Thank you for these words. You clearly knew his soul well.

I wish I could convey my thoughts and feelings as beautifully as that but I totally concur with your sentiments. Eugene may not physically be here but he is in a much more powerful way, through you, us and them. He was just magical. Much love.

Thank you for writing this. Should we all be so fortunate as to have a person like him in our lives (or be that person for another). <3

Thank you from my heart Derren for sharing your thoughts so incredibly. Your insights reflected Eugene’s life well lived – generously, mysteriously, on his own terms, and at the pinnacle of love for our art. He was the embodiment of passion: not just for performance, but for living. Eugene was the ultimate mentor – simplicity and complexity wrapped into one beautiful ball of yarn. I hear his deep voice still, and it resonates beautifully – it always will.

Thank you Derren.

I never had the opportunity to meet or admire Eugene and his work but what a magnificent eulogy you have written here. Sorry for your loss and for everyone’s loss.

I often wish I had the technical skills to do the magic that you do Derren. And if I had those skills, I would wish to have your performance ability. I would give anything to be able to paint like you. But if I could steal just one of your talents, it would be to be able to write like you. I don’t know how old Eugene was when he passed away, but he seemed a bit Dumbledore back when I was watching his instructional videos on VHS. Your piece is as elegant as ever and very moving. Thank you.

These thoughts you have shared on Eugene have struck a chord deep within, like so many I have been deeply inspired by his approach to magic and his philosophical writings. Your words are both comforting and inspirational – thank you Derren.

A touching astute and perceptive summation of an amazing man and a life lived the way it should be. Thanks for this Mr Brown

I loved every word of this. Thank you for taking the time to write it and share it, Derren.

Beautiful words for a beautiful man. I was lucky to have met him, only a couple of times, but every time I remember those days it makes me smile. I think it was impossible to meet him and instantly warm to him.

Damn I should proof things properly before submission. Of course I meant it was impossible to meet him and NOT instantly warm to him.

Perfect

Beautiful Derren, he’d be proud! Such a sad loss to our weird and wonderful art! I never had the opportunity of meeting Eugene but his magic and more importantly his attitude really inspired me from the beginning!

I never knew that he held prestigious degrees in religion and philosophy. Some magicians never cease to amaze. Derren, do you think that we can ressurect people in our minds even if we didn’t know them in life? I think so. I think love is better if shared in real time but it still has power to stretch the bands of death because all love is redeeming love. Reaching across time and space to love another person makes us better people. I wish I knew him but maybe in loving who and what he loved, I can.

Darren, you so perfectly captured the spirit and essence of this remarkable giant of the magic industry. He was my teacher my mentor, my inspiration. Nothing was more mesmerizing than sitting around a table with his magnificient presence, laying out his mystical carpet, lighting that candle, and beginning his phenomenal presentation of the gypsy thread. His voice is imbedded in my memory…I will always always remember and cherish my times with him… Jessica Bonvissuto

That’s the most true and beautiful remembrance I have ever read. Thank you.

Thank you Derren. This was lovely.

RIP

Derren,

Your heartfelt response to Eugene Burger’s passing is insightful, sensitive, and thought

provoking. No doubt, Eugene would have been grateful to you for submitting such a moving tribute. May his spirit continue to flourish in the lives of those who benefited from his influence.

By far, the most fitting tribute I have read. Derren, you are as eloquent as always and I feel the entire magic community should read this. Far more fitting than some of the things I’ve read.

Thank you for paying tribute with dignity and class. I was going to meet Eugene at the school in Vegas next summer and I looked forward to meeting him the most. You’ve reminded me that he’s still there in many ways. Rather than being bummed out and not going, now I’ve decided it’s imperative that I attend – even to walk the halls where he once played with friends and students alike.

Thanks, Derren.

thanks for sharing your memories and perspective, as ever

A wonderful tribute to Eugene, Derren. Thank you. He will be greatly missed….

James Randi.

Thank you Derren. My son , a magician of 18 years experience who always said that true magic was about creating a sense of wonder for people out of the mundane. What you said about Eugene and stories held true for him as well and in many aspects, perhaps the things you have beautifully described hold true for true artists in this field.

You said, ” When a life ends, there is no meaning: often only absurdity. We have to find that meaning for ourselves.” It seems too often we are told to accept the meaning that someone else puts on our loved one’s death… which seems akin to taking someone else’s medicine… quite dangerous.

Often our relationship with a loved one who dies has been built over many years (in my case 26) and when we have to create a different type of relationship with them ( when the loved can no longer answer when we talk to them) and with their memory, it must of necessity take time, sometimes beyond the patience of those well meaning caring people who urge us to “get on with our lives”. It in itself is perhaps a piece of art… part of the mystery that makes meaning in our lives.

you said that…” Eugene seemed to be a man in charge of his own story, yet mindful of its contingency within a world of deep mystery”. I like to think that this also characterized my son who was wise beyond his years. What a wonderful legacy that someone should live such that we can say that of them after their passing….. and that we can reflect on their lives and aspire to do the same.

my son died I believe as you described Eugene… ” as a man in charge of his own story”…. gravitas without solemnity… “A lifetime of loving and of gathering people together meant that he finished his life in the way he wished. He died very well.”

My son didn’t choose his brothers or his mother and father but he did choose a large group of close friends who described themselves as the “friend family” and who appear to care for each other in this way. After his death we his genetic family were amazed at the number of people who responded so passionately to the news… the outpouring of love from so many people in our regional community was staggering and we had no idea that he was so loved as a magician; a musician; an actor; a writer; a budding philosopher and a person who made people believe he cared for them and that they were important.

Like Eugene he …” knew that the self is not fixed but malleable, ambiguous and situated: it extends into the world…” and each person he encountered.” this is something for which I am so grateful. I as his father learnt so much from him as he say you did from Eugene. You said …”He is not absent: we can still find him in all of those people.” I find my son in all the people who responded and there were so many and they asked to a lasting connection with the family and each other. When we love someone who is alive we know them through the perceptions our mind receives and how we process those perceptions. When people die we still have those perceptions – its just that the person died doesn’t always have the same ability to surprise or delight us in new ways they did so before. We still have a relationship with them- but it changes from being a two way interaction between two minds to being the relationship we have between our own internal processes and our lasting impressions and memories. it can still be dynamic as we honour them- healing and creative.

I think this is what you meant when you said …”Those who were closest to him will recall and settle in their reveries of Eugene; they will now and then feel what it would be like to be him, to laugh at what he would laugh at, to react or raise an eyebrow or ponder a thought in his way. When they do, they will recreate in themselves the particular pattern, the unique twinkling consciousness that defined him. The more sympathetically they knew him, the more him it will be. And maybe this is where we find the Big M: perhaps it is something to do with the love between people that provides the mechanism for the self to survive death in the only meaningful way we know.”

Like Eugene, the world will never know the name of Benjamin J Wright (my son) as some of us who knew him would have liked them to. But it seems to me that Ben and Eugene were interested in quality rather than quantity. I am , as I believe you are , so grateful for their preference and for their living it in such a way so that they and the people around them had/have an enhanced opportunity to be constantly aware of the wonder that is possible in life.

I am sorry for your loss, but grateful for the opportunity you have afforded me to reflect and appreciate what our loved and admired ones create within us.

Derren–I just discovered your post and I’m humbled that you used one of my many photographs of Eugene. I am so fortunate that I was his friend for 40 years and that we were able to make so much visual magic together. He changed my life in so many ways; Eugene’s impact on the world of magic and beyond was huge and the reverberations of his voice will continue to spin out into the world for a very long time. I made a documentary on Eugene, A Magical Vision, and it’s out in the world of streaming if anyone wants to learn more about this amazing man. I miss him so much, but I’m so grateful that he was in this world and could speak about the power of magic and mystery.

Thank you for this, death is something I think about too much, I can’t get my head around the fact that it is infinite. Eugene Burgers books leave me feeling warm and good inside when most things about this art these days leaves me feeling a bit pissed off. Is there a place for good magic as entertainment anymore? I like making boxes. so I think I will continue to do that for the time being.